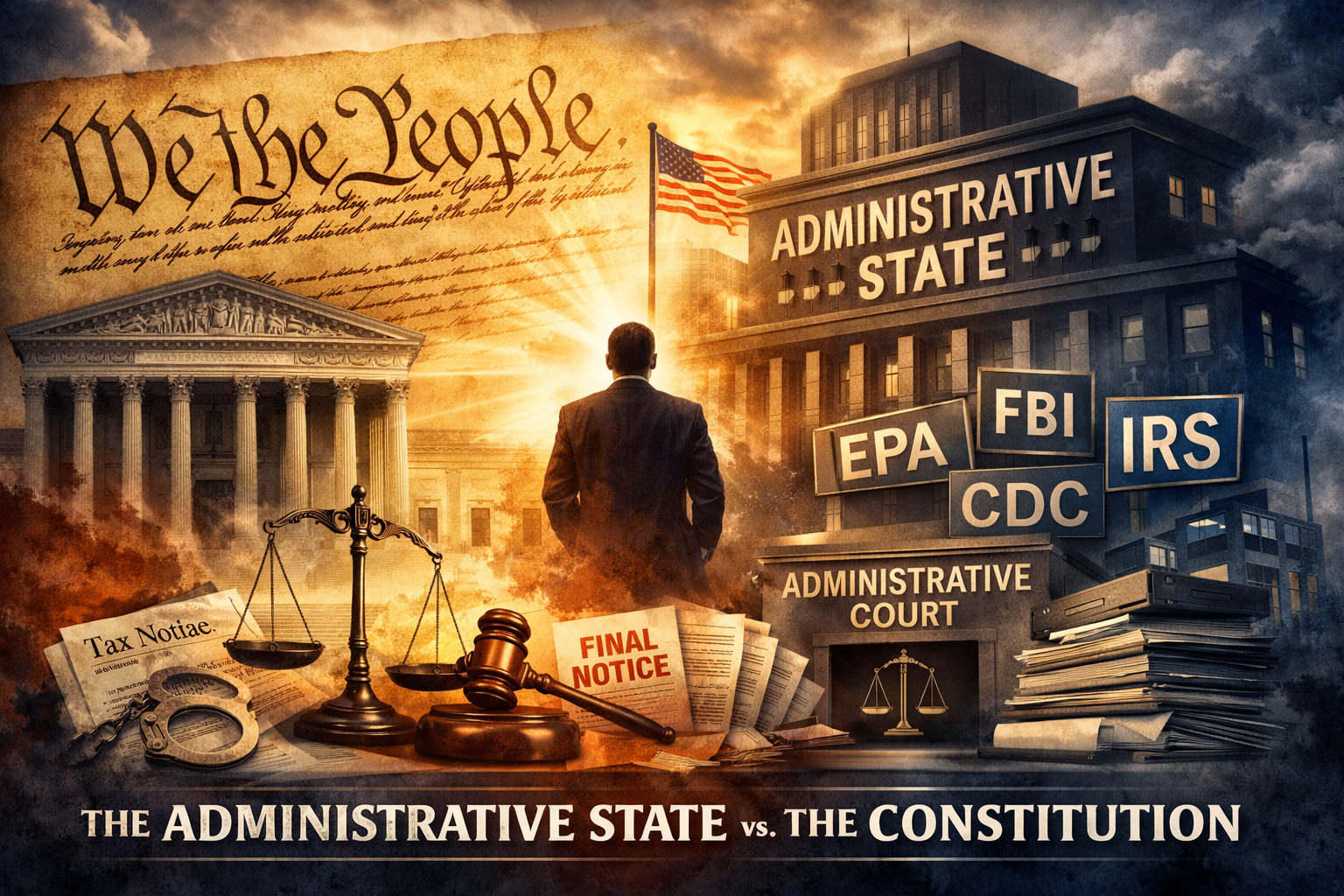

The Administrative State as a Constitutional Crisis

The central thesis is a serious one: that the modern administrative state has become a structural rival to the Constitution’s design. Framed in legal terms, the argument is that agencies routinely exercise blended powers—rulemaking, enforcement, and adjudication—in a manner that strains (and at times exceeds) the separation-of-powers architecture embedded in Articles I, II, and III. Whether one adopts the strongest anti-administrative position or a more incremental reform posture, the constitutional friction is real and now squarely back in the foreground of American law.

I. The Constitutional Baseline

The Constitution does not create a general “administrative” power. It vests legislative power in Congress (Article I), executive power in the President (Article II), and judicial power in the courts (Article III). Those vesting clauses are not ornamental; they are the core allocation provisions of the constitutional order. Article I’s opening clause is especially important because it vests “All legislative Powers herein granted” in Congress.

Madison’s warning in Federalist No. 47 remains the canonical statement of the separation principle: the accumulation of legislative, executive, and judicial power in the same hands is the “very definition of tyranny.” That principle is precisely why critiques of administrative consolidation are not fringe rhetoric; they are grounded in the original constitutional structure.

Modern Supreme Court doctrine also recognizes the constant institutional pressure for power to expand. In INS v. Chadha, the Court warned of the “hydraulic pressure” within each branch to exceed constitutional limits, even for seemingly desirable ends. That observation maps directly onto our concern that agencies tend to grow in scope and operational autonomy over time.

II. Why Critics Call It an Unlawful “Fourth Branch”

The administrative state is an “unlawful fourth branch.” In contemporary usage, that phrase captures a structural critique: agencies often (1) issue rules of general applicability, (2) investigate and enforce those rules, and (3) adjudicate disputes through in-house processes or administrative tribunals.

That description is not merely rhetorical. The Administrative Procedure Act (APA) expressly provides for agency rulemaking (5 U.S.C. § 553) and agency adjudication (5 U.S.C. § 554), with hearings conducted before agency personnel or ALJs under 5 U.S.C. § 556 and agency review under § 557. The APA also prescribes judicial review standards in § 706, including review for constitutional violations, excess of authority, and unlawful procedure. In other words: positive law openly recognizes an administrative apparatus that performs multiple government functions—while also trying to constrain it procedurally.

This is the key jurisprudential tension: the Constitution separates powers, but the APA regularizes multi-function agency governance. The entire modern administrative law project is, in part, an attempt to manage that tension rather than eliminate it.

III. Philip Hamburger’s Historical Argument: Administrative Power as Revived Prerogative

We will lean heavily on Philip Hamburger, and that is where the argument becomes historically potent. Hamburger’s position is not simply that agencies are inefficient or overreaching; it is that administrative governance revives a form of extra-legal prerogative that Anglo-American constitutionalism was designed to restrain.

In his historical account, kings acting through prerogative power bypassed ordinary legal channels. They ruled through decrees instead of statutes, enforced commands through prerogative courts (including Star Chamber), and expected judicial deference rather than independent judgment. Hamburger expressly draws the analogy to modern administrative practice: regulations, waivers, specialized adjudication, and deference.

He also frames the problem in structural terms: administrative power is “extra-legal,” “supra-legal,” and “consolidated” because it binds through mechanisms other than legislation and adjudication in constitutional courts, while also encouraging judicial deference to agency interpretations. Whether one agrees fully or not, that is a sophisticated constitutional indictment, not merely a policy complaint.

IV. The English Precedent Matters More Than Most People Realize

We shall appeal to English constitutional history is legally relevant. Long before the U.S. Constitution, English constitutional development struggled with prerogative courts and extra-parliamentary power.

Two historical anchors are especially important:

The Star Chamber became a symbol of prerogative adjudication and abuse; it was ultimately abolished in 1641. Historical sources note both its connection to royal prerogative and its abolition as a response to abuse.

The English Bill of Rights (1689) prohibited levying money for the Crown without grant of Parliament—an early anti-prerogative tax principle. Our tax-board example is clearly drawing from this lineage: the idea that taxation and coercive exactions must rest on lawful legislative authority, not bureaucratic improvisation.

This history does not automatically invalidate every modern agency. But it does show that the anti-prerogative instinct is deeply embedded in the constitutional tradition from which the American Constitution emerged.

V. Administrative Adjudication and Procedural Rights

The strongest constitutional pressure point in our discussion is procedural rights. The critique is that administrative tribunals can operate without the full protections associated with Article III courts and juries.

That concern has real traction in current Supreme Court doctrine. In SEC v. Jarkesy (2024), the Court held that when the SEC seeks civil penalties for securities fraud, the Seventh Amendment jury-trial right applies, and the case could not be finally resolved in the SEC’s in-house forum under the “public rights” exception on the facts presented there. That is a major decision because it confirms that not every agency enforcement action can be shifted into an internal adjudicative track free from jury protections.

Relatedly, in Lucia v. SEC (2018), the Court held that SEC administrative law judges are “Officers of the United States” for Appointments Clause purposes, reinforcing that agency adjudicators are exercising constitutionally significant authority—not mere clerical functions.

And in Axon Enterprise v. FTC (2023), the Court held that parties may bring certain structural constitutional challenges to agency proceedings directly in federal district court, rather than waiting to run the full agency process first. That ruling matters because it recognizes the gravity of structural objections to agency design and does not force every litigant to endure the allegedly unconstitutional process before obtaining judicial review.

Together, these cases do not abolish administrative adjudication, but they do show the Court tightening constitutional scrutiny around it.

VI. Deference, Chevron’s Fall, and the Return of Judicial Judgment

I think it only right to also attack judicial deference to agencies. That argument has become dramatically more salient after Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo (2024), where the Supreme Court overruled Chevron and held that courts must exercise their own independent judgment on whether an agency has acted within statutory authority, as the APA requires.

That is a major doctrinal shift. It does not mean agencies lost all interpretive influence; Loper Bright still recognizes that Congress can delegate discretion within constitutional limits. But it does mean courts are no longer supposed to reflexively defer simply because a statute is ambiguous. In constitutional-structure terms, that shift directly supports our concern that deference can convert agencies into quasi-supreme interpreters of their own power.

VII. Nondelegation and the “Major Questions” Constraint

We must argue that agencies are effectively making law. Existing doctrine has long tolerated significant delegation, but the Court has also repeatedly recognized constitutional limits.

In Gundy v. United States (2019), the Court reaffirmed the nondelegation issue as a live constitutional principle, even though the statute there survived. The proposition that Congress cannot simply transfer legislative power wholesale remains part of the doctrine’s foundation.

In West Virginia v. EPA (2022), the Court applied the major questions doctrine to limit an agency’s assertion of broad power over a matter of vast economic and political significance without clear congressional authorization. The doctrine is explicitly tied to separation-of-powers and federalism concerns.

So while the nondelegation doctrine has not (yet) invalidated the modern administrative state wholesale, major-questions jurisprudence and recent cases are functioning as a partial substitute—requiring clearer legislative commands before agencies may exercise highly consequential regulatory authority.

VIII. The Tax-Board Example

Let us end with a tax-board scenario: a citizen receives a demand for information, ignores it, then faces a large assessment based on a “statistical model,” followed by threatened collection through liens. As presented, the example is meant to illustrate how agency power can become coercive, self-justifying, and procedurally asymmetric.

As a legal matter, that example should be treated carefully. State tax procedures vary, and tax administration often operates under statutory assessment and collection frameworks that differ from ordinary criminal procedure. So the strongest legal critique is not a blanket slogan, but a procedural one: whether the agency had lawful statutory authority, adequate notice, a proper factual basis, and constitutionally sufficient process before depriving property. The Fifth Amendment’s due process guarantee remains the controlling constitutional baseline for that inquiry.

That said, our larger point stands: when agencies both generate the operative rules and control the initial enforcement and adjudication channels, the risk of overreach increases unless courts rigorously enforce statutory and constitutional limits.

IX. Why This Debate Is Intensifying Now

This is not a marginal academic debate anymore. It is accelerating because the Court has recently:

curtailed deference (Loper Bright),

strengthened jury-trial protections against in-house penalty adjudication (Jarkesy), and

opened district-court access for structural agency challenges (Axon).

At the same time, federal governance still depends on a vast agency infrastructure, and even official drafting guidance reflects the scale and complexity of the administrative apparatus (the Federal Register’s drafting materials note hundreds of agency and subagency acronyms). So the legal system is not exiting administrative governance—it is entering a period of constitutional recalibration.

Conclusion

Operation Wisedome’s broad claim—that the administrative state presents a profound constitutional problem—tracks a serious line of constitutional thought, not mere political rhetoric. The Constitution’s text, the separation-of-powers tradition, anti-prerogative English history, and recent Supreme Court decisions all support closer scrutiny of consolidated agency power.

The harder legal question is remedial, not diagnostic: what should replace or restrain the current model? On that, the emerging answer appears to be a combination of stricter judicial review, clearer congressional legislation, narrower delegations, stronger procedural protections, and renewed insistence that constitutional structure is not optional. That is where the next phase of this fight will be won or lost.