The Bill of Particulars as a Due‑Process Scalpel

in Maryland Traffic‑Citation Prosecutions

I. The problem: “labels” are not notice

Maryland criminal practice does not tolerate charging by mere conclusion—especially where the State seeks to convert an ordinary roadside encounter into a multi‑count prosecution. The constitutional obligation is elemental: a defendant must receive reasonable notice of the accusation and a meaningful opportunity to defend. In re Oliver recognizes notice and the opportunity to be heard as a bedrock of due process. Justia Law

Maryland’s own jurisprudence is equally uncompromising. Article 21 of the Maryland Declaration of Rights protects the accused’s right “to be informed of the accusation,” and Maryland charging practice has long required that the State not only characterize the crime but also describe the specific conduct alleged. Dzikowski v. State collects and reaffirms that doctrine, citing Ayre, Morton, Williams, and Jones for the proposition that a criminal charge must (i) put the accused on notice of what he must defend, (ii) protect against double jeopardy, and (iii) enable trial preparation, among other functions. Justia Law

II. The rule: essential facts, time, place—not conclusory shortcuts

Maryland Rule 4‑202(a) codifies what due process already demands: a charging document “shall contain a concise and definite statement of the essential facts” and, “with reasonable particularity,” the time and place of the offense. Maryland Courts

When citations are drafted in an indefinite or formulaic manner—e.g., “unsafe vehicle” without identifying the allegedly unsafe component; “suspended registration” without identifying the suspending authority, the effective date, and the specific registration—then the defendant is denied the very notice Rule 4‑202 requires.

III. The Bill of Particulars: what it is (and what it is not)

A bill of particulars is not a discovery device and not a demand that the State divulge its legal theory in the abstract. It is a due‑process tool that forces the prosecution to tie the charge to the conduct it claims constitutes the offense, thereby limiting surprise and constraining proof.

Maryland’s high court is explicit: a bill of particulars “must, at the very least, provide the defendant with a means of ascertaining the exact factual situation upon which [he] was charged.” Justia Law And, critically for modern “open file” gamesmanship, Dzikowski holds that directing the defendant to discovery is not responsive and cannot substitute for a legally sufficient bill of particulars—because discovery does not reflect the State’s own “perspective and relation of factual information to the offense charged.” Justia Law

Moreover, Rule 4‑241(b), as quoted in Dzikowski, requires the State (upon a proper demand) to file a bill of particulars within ten days or state the reason for refusal. Justia Law

IV. Applicability in Maryland courts (District Court posture)

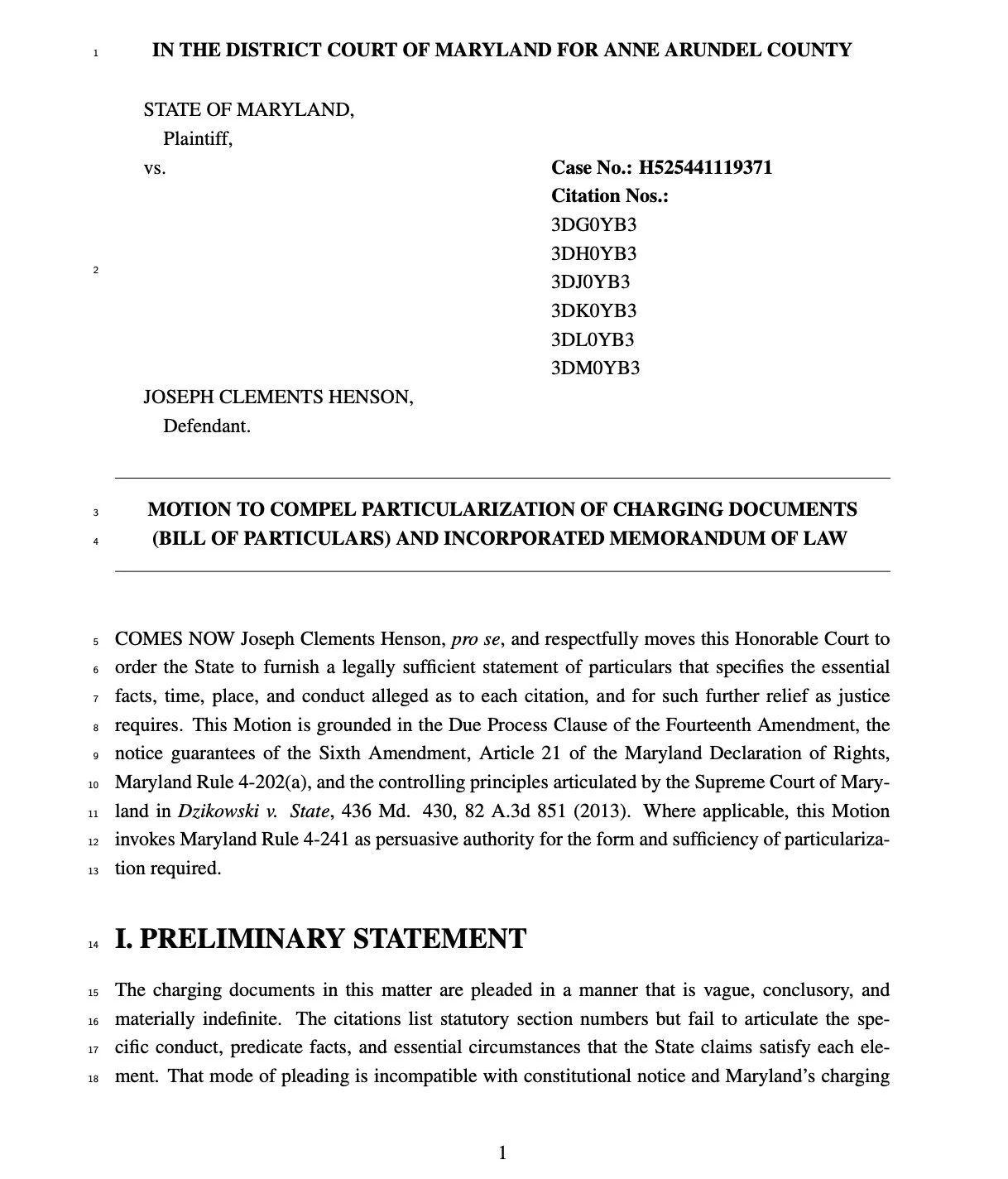

Although Rule 4‑241 is captioned for circuit‑court use, Maryland’s Rules framework provides that Title 4 applies to criminal matters in both the District Court and circuit courts. Maryland Courts For traffic‑citation proceedings that remain in District Court, the strongest practice posture is to style the request as a motion to compel particularization of the charging documents grounded in Article 21, Rule 4‑202(a), and Dzikowski’s constitutional notice principles—and to invoke Rule 4‑241 as persuasive authority where the court chooses to employ it by analogy.

V. Why this matters in traffic‑citation prosecutions: six counts, one stop, and the State’s burden to articulate

Consider a common pattern: a stop justified by little more than a hunch (or an out‑of‑state tag), followed by stacked citations:

TA § 13‑703(g) prohibits displaying a plate that is neither “issued for the vehicle” nor “otherwise lawfully used” under Title 13. Maryland General Assembly

TA § 13‑401(h) forbids driving where “the registration of a vehicle is suspended.” Maryland General Assembly

TA § 13‑401(d) forbids driving if the required registration fee “has not been paid.” Maryland General Assembly

TA § 13‑403(a)(1) requires an owner of a vehicle “subject to registration under this subtitle” to apply for registration. Maryland General Assembly

TA § 13‑101.1 requires an owner of a vehicle “in this State” (for which Maryland has not issued title) to apply for a Maryland title—subject to enumerated exceptions. Maryland General Assembly

TA § 22‑101(a)(1) prohibits driving a vehicle in an “unsafe condition” endangering any person or lacking required equipment. Maryland General Assembly

In an out‑of‑state registration scenario, the State often glosses over the statutory predicate question: Was the vehicle actually subject to Maryland registration and titling requirements at the time? Maryland provides explicit nonresident exceptions allowing a nonresident to drive a “foreign vehicle” without Maryland registration if (among other conditions) it displays current plates from the owner’s place of residence and is not regularly operated in carrying on business in Maryland, and is not in the custody of a resident for more than 30 days during any registration year. Justia Law

If the prosecution’s theory is “you were actually a Maryland resident,” or “the vehicle was regularly operated in business,” or “custody exceeded 30 days,” it must identify the facts supporting that predicate—not simply recite the section number.

VI. The Fourth Amendment overlay: the stop itself must rest on articulable facts

A bill of particulars is also a strategic bridge to suppression and dismissal litigation: it requires the State to articulate what facts it claims existed at inception.

Delaware v. Prouse condemns “random” traffic stops absent “specific articulable facts” supporting reasonable suspicion of a violation. Justia Law

Whren holds that a traffic stop is reasonable when officers have probable cause to believe a traffic violation occurred—yet it does not bless stops without an articulable violation. Justia Law

Rodriguez bars prolonging a stop beyond the time needed to address its mission absent independent reasonable suspicion. Justia Law

A well‑drafted demand can force the State to pick a lane: what exactly was observed, when, how confirmed, and how the stop’s scope remained lawful.

VII. Body‑worn camera compliance: not a “gotcha,” but an integrity issue

If the agency’s own written directive requires event‑mode recording at the initiation of enforcement encounters—including traffic stops—then activation time and any failure‑to‑record rationale are plainly relevant to credibility, completeness of the State’s narrative, and potential spoliation/inference issues.

Anne Arundel County Police Department Written Directive Index Code 1904.4 states that event‑mode recording “must be utilized” at the initiation of enforcement encounters, expressly including “traffic stops,” and if recording cannot begin at initiation, it must begin at the first reasonable opportunity. PowerDMS

VIII. Strategic framing: “chess, not checkers”

Civil litigators often prefer mechanisms that force early commitment and finality. A Rule 12(c) motion, for example, is prized because it can culminate in final judgment rather than a mere dismissal without prejudice. Chess not Checkers_ Why Litigan… The analog in the traffic‑citation context is not procedural identity—it is strategic posture: compel the State to commit to facts early, narrow proof, and constrain later pivoting.

IX. Practice tips: how to draft demands that courts actually grant

Target elements, not “all evidence.” Dzikowski reiterates that a bill specifies particulars of the offense charged, not every evidentiary detail, and it is not an instrument to force the State to “elect a theory.” Justia Law

Demand the “exact factual situation.” Ask for time, place, actus reus facts, and the statutory predicate facts (e.g., residency/custody/business‑use facts for out‑of‑state registration cases). Justia Law

Link the demand to Rule 4‑202’s requirements. If the citation is deficient on its face, say so, and request particularization as the cure. Maryland Courts

Ask for an order limiting proof. The true utility is preclusion: if the State later tries to prove a different factual scenario than the one particularized, you have an enforceable constraint grounded in due process and Dzikowski. Justia Law